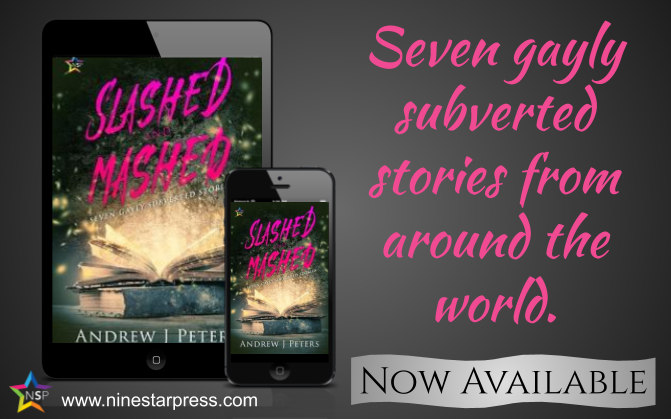

Title: Slashed and Mashed: Seven Gayly Subverted Stories

Author: Andrew J. Peters

Publisher: NineStar Press

Release Date: November 11, 2019

Heat Level: 3 - Some Sex

Pairing: Male/Male

Length: 96700

Genre: Fantasy Folklore, LGBT, retold lore/folklore, fantasy, mythical creatures, magic, magic beings, magical reality, trickster, action/adventure, established couple, over 40, Greek mythology, Hungarian folklore, Grimm’s fairytales, Momotarō, historical fiction, jaguar folklore, the Arabian Nights, African folklore, Uncle Remus.

Add to Goodreads

Synopsis

What really happened when Theseus met

the Minotaur? How did demon-slaying Momotarō come to be raised by two daddies?

Will Scheherazade’s hapless Ma’aruf ever find love and prosperity after his

freeloading boyfriend kicks him out on the street? Classic lore gets a bold

remodeling with stories from light-hearted and absurd, earnestly romantic,

daring and adventurous, to darkly surreal.

The collection includes: Theseus and the

Minotaur, Károly, Who Kept a Secret, The Peach Boy, The Vain Prince, The Jaguar

of the Backward Glance, Ma’aruf the Street Vendor, and A Rabbit Grows in

Brooklyn.

Award-winning fantasy author Andrew J.

Peters (The City of Seven Gods) takes on classical mythology, Hungarian

folklore, Japanese legend, The Arabian Nights, and more, in a collection of

gayly subverted stories from around the world.

Excerpt

Slashed and Mashed

Andrew J. Peters © 2019

All Rights Reserved

THE GREAT HALL of the king’s palace was

vast enough to house a fleet of double-sailed galleys, and its gray, fluted

columns, as thick as ancient oaks, seemed to tower impossibly beyond a man’s

ken. Prince Theseus had been told, he had been warned of the grandeur of the

Cretans, how it was said they were so vain they forged houses to rival the

palace of Mount Olympus. Yet to see was to believe. For a spell, the sight of

the great hall stole the breath from his lungs and slowed his feet to a

stagger. Should not he, a mere mortal, prostrate himself on his knees in a

place of such divine might, such miraculous invention? It felt as though he had

entered the mouth of a giant who could swallow the world.

No, he reminded himself: this was all

pretend, a trick to frighten him and his countrymen, though he only half

believed that. Silenos, an aged tutor who Theseus’s father had hired to teach

him all things befitting a young man of the learned class, had cautioned him

not to trust his eyes, that these pirates of Crete used their riches to build a

city of illusions so any navy that endeavored to alight at its shores would be

hopelessly confounded and turn back to sea in terror.

Theseus forced a swallow down his

bone-dry throat and retook his steps to keep pace with the soldiers who

escorted his party into the hall. He had brought his father’s highest-ranking

admirals to accompany him, Padmos and Oxartes, and the king had sent three men

for each one of them to meet them at the beach where they had rowed ashore.

From there, they had been conveyed up a steep, zigzagging roadway to the

palace. The armored team looked like an executioner’s brigade rather than a

diplomatic corps. They were hard-faced warriors clad in bronze-plated aprons

and fringed, blood-red kilts, and they carried spears that could harpoon a

monster of the ocean.

He tried to look beyond the many wonders

and train his gaze on the distant dais where the king and his court awaited

him. Yet curiosity bit at Theseus. Oil-burning chandeliers seemed to hover in

the air, hung from chains girded to a sightless ceiling. No terraces had been

built to bring in daylight, nor doorways to other precincts of the statehouse,

unless they were hidden. Theseus would say it smelled of nothing but damp stone

and clay, the cool, cloistered air too sacred to be disturbed by perfumes. The

walls shimmered with a metallic reflection of the room’s massive columns,

affecting the appearance that the hall went on to infinity. The

diamond-patterned carpet on which he trod was one continuous design stretching

from the vaulted doorway where he had entered all the way to the other end.

Such a carpet was surely large enough to cover the floors of every house in

Athens!

As he neared the stately dais, he beheld

the king’s high-backed throne of ebony and glimpsed the man himself along with

the shadowy members of his court. Theseus lowered his gaze to disguise his

impressions. He supposed it also counted as a gesture of respect. He followed

the soldiers into a lake of light that glowed from thick-trunked braziers on

either side of the hall’s carpeted, shallow stage.

Their steps ended some ten paces in

front of the room’s dignitaries, including, of course, the king himself. The

armored men knelt on one knee, drummed down the handles of their spears on the

floor, and bowed their helmet-capped heads as one company.

That left Theseus and his consorts

standing and wondering what to do with themselves for a worrisome moment. To

kneel to the king was to surrender Athens’ sovereignty, and that had not been

his father’s bargain. Though his princely leather cuirass and his laurel crown

felt peasant-like, almost absurd while he stood before the king, Theseus did

not break. He glanced to Padmos and Oxartes so they would know they should

neither kneel nor bow.

Righteousness grew inside Theseus,

arisen from the unsurpassed conviction of a youth of eighteen years who felt

well-acquainted with the indignities of the world, though in truth had rarely

been cut down to size. As an infant, he had been sent to live in his mother’s

village, which was countries apart from the hubbub and political fray of

Athens. This, no excess of fatherly protection, but a testament to his father’s

severity. People later spoke of his banishment in the ennobling light of

superstition, an augury of the night sky or some such according to his father.

In any case, Aegeus had decreed: if his son was worthy to succeed him, he must

earn the right on his own terms.

For most of his life, Theseus had not

known his father. He had not even known of his paternity, though he had lived

quite well as a handsome, rugged lad among countryfolk who required no more

than that to smile upon him, fetch him apples, give him a rustle on the head

when he passed by, a proud acknowledgment he was one of their own. Then came

his mother’s confession, and his storied trek to present himself at his father’s

court, which he had made on foot across Arcadia, an ungoverned, forested land

that had been said to be rampant with all manner of bandits, ogres, and

mythical beasts.

In Athens, he was a newcomer, an

adventurer, and a fawn-haired swain, all of which earned him magnanimous

gossip. Men made way for him, and women smiled and idled when he passed by.

Naturally, young Theseus was aware of

none of this, as a favored flower does not question why it thrives in sunlight

and has a gardener always at the ready for its succor, while others of its kind

turn spiny and dull from negligence. Or, it should be said, a glimpse of his

place in the world, past and present, was only just then taking form while he

stood in King Minos’s great hall. He did not like how it made him feel.

He shook off the sinking sensation. He

would be bold, for he alone stood for Athens in this house of tyranny. As he

had heard, these foreigners had butchered his countrymen, raped their women,

taken their daughters and sons as slaves, and burned their fields. He would end

the war, and it did not matter if he returned to Athens on a white-sailed

galley to herald a hero’s return or if a black-sailed ship should come back to

his father, signaling that Crete had been his final resting place. So had he

decided. He looked to King Minos to begin.

The Cretan king returned his gaze,

appraising, taunting, and then he perched in his seat and craned his neck to

see beyond the prince, to turn a querulous eye at the headmen of his squadron.

“Where is Athens’ tribute?” he spoke.

He appeared to be no more advanced in

years than the prince’s father, a sturdy, dispassionate age. The similarity

wore through at that. The king’s chestnut-brown beards were plaited and shone

with oil, and he wore a miter banded with red-gold. He was clad in deep

cerulean raiment of the finest dye and a draped, red stole, all adorned with

fine embroidery and fringe. Theseus had never seen a man so richly clothed and

groomed. His father, the wealthiest man in all of Attica, had only a sheep’s

fleece and a laurel crown to say he was king.

“King Aegeus has sent me, his son,

Theseus of Attica, to answer your request,” Theseus spoke.

Minos pursed his lips, sucked his teeth.

“I asked for children.”

That was the compact signed by Theseus’s

father to end the war—seven boys and seven girls surrendered to Minos in return

for nine years of peace, during which the Cretan king had pledged he would call

back his warships.

It was a war begun while Theseus still

lived with his mother in the countryside, years before she had taken him to an

unfarmed field outside the village and shown him his father’s buried sword,

from which he came to know his origins. Theseus had only arrived in Athens one

season past and been apprised of the history. This heartless war borne from a

tragic misunderstanding.

Two years ago, Minos sent his son

Androgeus to Athens on a friendly embassy, and when Theseus’s father took the

youth on a hunt to see something of his country’s pastimes, Androgeus was

thrown from his horse and landed headfirst on a rock. No physician nor priest

could restore him. His spark of life had been extinguished all at once.

Aegeus returned the prince’s body to

Crete with all due sacraments and respects. He had been washed to prepare him

for his passage to the afterworld, and the king sent him across the sea on a

bier of sacred cypress, ferried on his finest ship, oared by his best sailors,

and with a bounty of funereal offerings, gold and silver, many times more than

his kingdom could afford. Yet Minos declared treachery and turned fire and fury

against Athens.

Three seasons the war had raged, and

after a decisive battle on the Saronic Gulf, Minos claimed the vital sea

passage and installed a naval blockade, robbing Athens of her trade routes and

slowly starving her. Aegeus appealed to the Cretan king for an armistice. An

emissary from Crete returned with the tyrant’s reply: fourteen innocent lives

for the price of his son. This, after Crete had already extracted the lives of

thousands of fighting men in payment for Androgeus, whose death could only be

blamed on the mysterious Fates.

Aegeus decided he had no choice but to

agree to the king’s terms, and his council supported him. The Athenian navy was

no match for the foreigners neither by the numbers nor by the craftsmanship of

their vessels. The Cretans flung barrels of fire from catapults. Their triremes

were faster and their battering rams were more potent, carving apart a galley

on a single run. The Athenian fleet had dwindled to a dozen vessels. Their

forests were stripped of lumber, and even if they had the resources, their

shipbuilders could not assemble new warships fast enough. Food shortages had

depleted their force of able-bodied men to defend the city. Without a reprieve

from war, the next attack on Athens would be the last. Who could stop an army

empowered by the God of the Sea?

But after the lottery had been held, and

weeping fathers from all parts of the country brought their sons and daughters

to the naval pier where they would be ferried to Crete, Theseus could not bear

it. He looked upon the children, stunned as lambs without their mothers, and

wept for them, and wept for his country, and wept for the shame of being part

of this abomination.

Then, in a rush of rage, Theseus

attacked the sailors who would lead the children to the ship. He had come to

know them as friends, yet all he saw were blank-faced monsters. By grace, he

had only had his fists, and no man raised a blade to stop him. Theseus shoved,

struck, and menaced perhaps a dozen before they overtook him and held him fast

by his neck and arms. A terrible blackness ate up his vision, and, inspirited

with a daemon’s strength, Theseus threw off his captors. He turned his fury at

his father who stood at the landside end of the quay with his councilors.

Theseus shouted at them vicious oaths he

had not known were in his vocabulary, and he spat at them. Did they not know

what they were doing was an offense to the goddess? It was a betrayal of every

free man of Attica. His throat was scorched from shouting, his voice hoarse,

and he fell to his knees, dropping his bonnet, weeping and pulling at his

thick, curled hair.

He looked up at his father. “Please,

send me.”

Now Theseus faced King Minos intrepidly.

“I have been chosen to stand for the children. I have only eighteen years,

turned just this past season, and I am my father’s only son. I will face your

contest.”

Purchase

NineStar Press | Amazon | Smashwords | Barnes & Noble

No comments:

Post a Comment